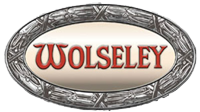

Alan Elmslie’s 1936 25 H.P. Super Six Saloon

Written By Malcolm Elmslie

Editor’s Note: We met with Malcolm Elmslie at the Bermagui Rally in Australia in March. His father Alan bought a 25HP Saloon brand new in 1936, and Malcolm has written this article and supplied photos copied from the family album for Wolseley enthusiasts to enjoy.

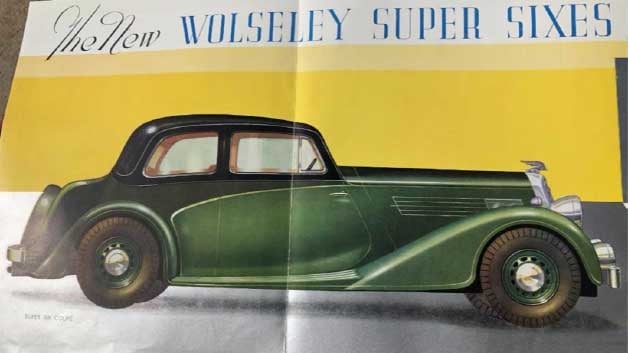

The restrained modernity that British taste in bodywork has now fully endorsed finds perfect expression in the graceful sweeping lines of the new WOLSELEY Super Sixes. They are eloquent also of power — power translated into terms of flawless performance — power that flashes or soothes as the driver demands. In the opinion of qualified judges these cars are the most significant in the motoring world today — cars built in the best British fine-car tradition, yet selling at prices that only WOLSELEY’S coordinated methods of craftsmanship production have made possible.

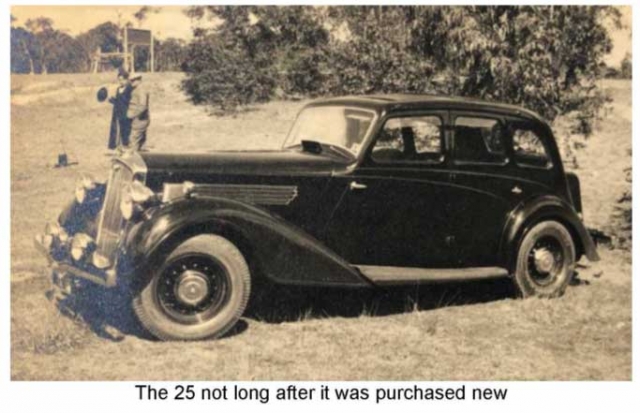

So says the brochure my father received from Dalgety & Company Limited, of 136 Phillip Street, Sydney when he was seeking to buy his next car in 1936. He and his father had already owned several different makes, including Citroen, Rover, Standard, and Austin, but this time it was the Wolseley Super Six Saloon that caught his eye. He had already owned it for several years when I came into the world, and from then until he sold it in 1962, it and my mother’s 1937 Hillman Minx were our family cars.

In May of this year, I had the pleasure of meeting and greeting a collection of Wolseley’s and their owners during the 2019 National Rally to Bermagui. In the course of their stop for morning tea in Cobargo, I showed around some brochures and photos from my parents’ albums. On seeing what I had, John Mallia then suggested that I might like to put together some of my reminiscences of my father’s car.

My earliest memory of the Wolseley was soon after the end of the war when Dad completely rewired it and gave me the old coloured wires to play with. He was an engineer and very proficient in car maintenance and repairs. During the war, while Dad was away, petrol was virtually unobtainable for private use, so the Wolseley was put up on blocks in the garage. I remember the gas producers that some car owners, unable to obtain petrol, had fixed on the backs of their cars, and the gas bag the local taxi had on its roof. Rationing of petrol continued for some years after the end of the war.

A very important part the Wolseley played early in my parents’ years together was to take them from Sydney to South Australia on their honeymoon. This was not long after BlackFriday — the 13th of January 1939 — when bush fires engulfed Victoria. According to Dad, during this trip, the car achieved a top speed of 86 mph (138 kph) along the Coorong. Before this, however, the Wolseley had been on some long trips.

In September of 1936 – the year he bought it – Dad and his mother went on a trip to Canberra. Accompanying them on this tour was my future mother with her mother and brother in their Dodge. By the time they were married, Mum had acquired a 1937 Hillman Minx.

To digress a bit, my two grandfathers were each other’s oldest friends, being the same age, and having met when they were in their twenties in Townsville. Going their separate ways but staying in Queensland, each got married in Brisbane and lived there, later moving to Sydney, where Dad and Mum grew up — and eventually undertook the aforementioned honeymoon trip to South Australia.

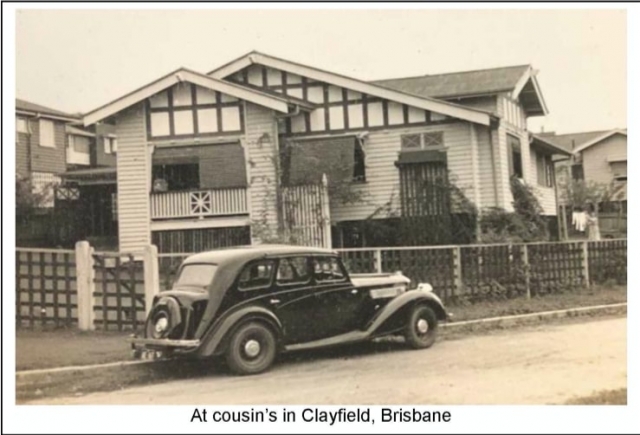

Before he was married, Dad took the car north on his own, visiting cousins in Brisbane, then going on to the Bundaberg area to visit more cousins. There were also trips to the Blue Mountains and the Southern Highlands — anywhere he could put the car through its paces and show off its performance.

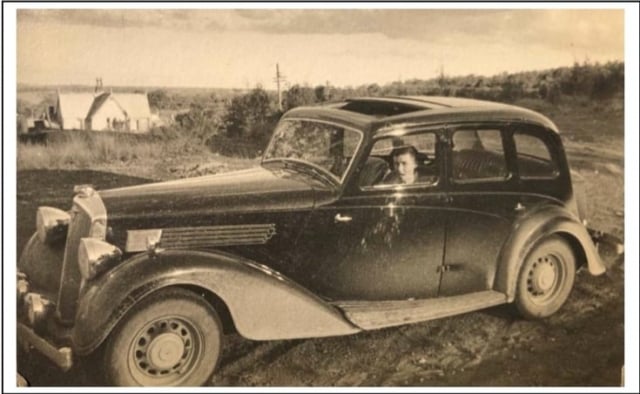

Dad was a great believer in teaching young people to drive at an early age, and before I was 10 years old I used to be allowed to take the car from the garage to the front gate. When I was 11 or 12, Dad took my sister and me “out west”.

He loved the hot inland regions, having cousins who lived on a million and a quarter acre property near Bourke, where they used to play tennis when it was “120 in the shade.” On this trip, Dad had been hoping to get to Warren to look up an old army colleague, but after “doing a big end” we only got as far as Trangie.

The problem with the big end meant that we had to limp back to Sydney; any speed over 30 mph was met with a banging noise. Driving home, Dad was constantly putting his arm out the window waving people to pass us. Besides this problem, we also broke a rear axle not long after leaving Sydney, near Blackheath if my memory serves me correctly.

This was something Dad had to put up with often, so he always took along at least one spare rear axle on any long trips. I drove 100 miles on this trip, and my sister, three years my junior, “drove” 10 miles sitting on Dad’s lap, as she couldn’t reach the pedals.

It did not happen on this trip, but during the hotter months we not infrequently experienced a problem with the twin electric carburettors. If the car was going uphill loaded or pulling a trailer, the carburettors would sometimes cut out. All that could be done was to stop and let them cool down. Sometimes just giving them a bit of a knock did the trick.

Dad was in the habit of starting in second gear if the road was not too steep. He was not an aggressive driver, but very few other drivers, if any, could beat him away when a traffic light changed to green.

In 1939 Dad became a member of The Australian Company of Veteran Motorists. Its rules required its members, who had to have an excellent driving record, to “observe the accepted rules of the road, and by example to others contribute to the safety of the highway.” A sticker for the car’s rear window was given to members “to show overtaking vehicles that the car in front is driven by an experienced driver.”

By 1943 the name had been changed to The Veteran Motorists of Australia (VMA), by which time there were 322 members in the New South Wales section, Dad being no. 99. By 1949 the number of members had risen to 717. The objects of the Association were (inter alia): (a) to band together experienced motorists with clean driving records, and (b) to promote a high standard of safe driving and good road manners. Members had to have held a driving licence for at least 15 years. In the 1949 list of members, Dad had held a licence for 31 years.

Later, in 1962, the Advanced Motorists Chapter of VMA was set up. Members of VMA could undertake an advanced driving test, the hope being that this may go some way to effecting “a realistic reduction in the appalling toll on the roads.”

Dad was proud to have been accepted into the AMC, and he displayed the two badges on the front of the car.

Hardly any people who saw the badges on the car were aware of the existence of these two organisations, VMA and AMC. People invariably thought the VMA badge was a simple M, and only after it was pointed out did they see that it was V and M superimposed.

Although it was after he had sold the Wolseley that he became a member of AMC, I mention it here in case someone reading this may have heard of it, and the VMA. I do not know what happened to these two organisations.

At first, the car had the NSW number plate 182-160, but when plates with two letters and three numbers were introduced sometime before 1939, he procured AE-166 for Mum’s Hillman and AE-167 for the Wolseley. In those days you could not ask for a certain number plate; you had to know someone who would tell you when number plates with the letters you were after were about to be issued. AE-167 eventually got so faded and unreadable that it had begun to attract the attention of police. It was not possible then to have a number plate remade, or maybe it cost too much, so Dad got a new yellow and black number plate AFK-559 for the Wolseley, which it still bore when he sold it.

According to Dalgety’s 1936 price list, the 25 h.p. English saloon, 5-passenger 121/2 inch wheelbase, cost £599 plus £25.9.0 sales tax. There was also a De Luxe Australian saloon, which was the same car but with an Australian body, which cost £515 plus £21.2.3. Dad’s was the fully imported English model, black in colour.

Among notable features of the car was the hydraulic jacking system, whereby the car could be jacked up, either two wheels or all four wheels, by working a lever between the driver’s seat and the door while sitting in the car.

We also had a picnic table that fitted into slots behind the front bucket seats for the back-seat passengers to use, and another small removable shelf for the front-seat passenger. I am not sure whether these were standard or whether they were an optional extra. I do not think they were home-made.

One feature of the car that was a bit of a drawback was the poor luggage space. The boot was only accessible from inside the car by lifting up the back of the rear seat, as the spare tyre on the back of the car prevented access from outside the car. This is why Dad bought a trailer. It was the only way we were able to go to our beach house for school vacations. We even once took our dozen or so hens in a cage with us in the trailer — it was a large steel trailer, and even had its own number plate and registration sticker.

While the Wolseley’s luggage space left something to be desired, the Hillman’s boot was accessible from outside the car. However, the Hillman’s tail light could only be switched on from outside the car by pulling up a little toggle on the back of the car.

Five people could easily be accommodated in the car without discomfort. In fact, occasionally there were six people, but this meant that one person had to sit on a cushion on top of the hand brake. Another time I remember there were nine children in the car being ferried to some sporting event or other. What times they were!

From memory, the Wolseley had done over 200,000 miles before Dad decided that he wanted a new car. This was 1962. There was no thought of keeping it until it became a classic or vintage car; it was simply an old car, albeit only 26 years old.

The brown leather upholstery was showing its age, and the front passenger’s seat was never the same after a friend of the family who was not small managed to pull it from its mountings when she plopped herself down in it rather heavily.

It was also becoming increasingly difficult to get spare parts; some had to be procured from England. I was not living at home at the time and had little say in the matter, and anyway I was more interested in real veteran cars — 1916 or earlier.

So the Wolseley passed out of our lives. I had assumed until recently that it would not have been preserved, but my sister remembers seeing it somewhere around the northern beaches in Sydney after Dad got rid of it, so maybe it was sold to an enthusiast, but I doubt Dad got much for it if anything.